Introduction

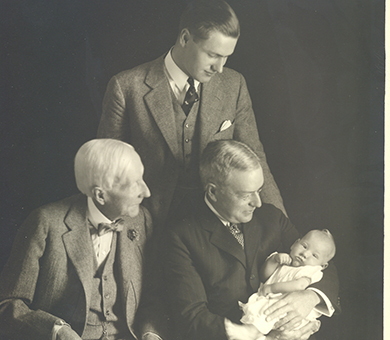

For the Rockefellers, giving has been a central family value that has spanned three centuries.

The strong belief of early generations that wealth comes with great responsibility continues to inform the philanthropy of current generations, helping to shape their priorities and perspectives on giving. The family is now entering its seventh generation and has maintained its tradition of giving within each generation.

Inspiration

Inspiration

John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (JDR) was born with the entrepreneurial spirit of his father, a farmer and patent medicine salesman, and the religious-driven generosity of his mother, Eliza Davison Rockefeller. Mrs. Rockefeller was a pious Baptist who taught her children to tithe, a tradition of giving 10 percent of one’s income to the church, that was passed down to subsequent generations. JDR was heavily influenced by his mother’s charitable practices and began his own giving the very first year that he started working, when he made just $45 a year.

JDR became involved in the petroleum industry, soon founding Standard Oil, which would become the dominant oil company in the United States. With the great success of Standard Oil, JDR explored new purposes for his unprecedented wealth. In addition to making many investments in different sectors of the American economy, he also allocated a significant portion to charity.

From 1855, when JDR gave his first philanthropic gift, until almost the turn of the 20th century, Rockefeller’s giving was spread across many individuals and institutions and largely focused on the Baptist church itself and universities founded as Baptist institutions, such as the University of Chicago and Spelman College. While this religious-driven giving certainly highlights JDR’s strong ties to the church, it also signifies the early state of the nonprofit sector at the time: There were few other secular organizations that he could have given to.

Central Themes

Guiding Principles

There are several central themes in the Rockefeller family’s giving that could be applied to other families hoping to develop thoughtful, planner multigenerational philanthropy:

The family shares a sense of duty to improve the common good and a responsibility to humanity.

Family traditions play a critical role in the transmission of these values from generation to generation.

The family recognizes that philanthropy becomes more meaningful when personal experiences create opportunities to give to a cause that resonates with family values.

Action

Action

Although JDR’s giving was, at first, very narrow, he was soon overwhelmed by the sheer volume of request letters that he received from individuals all over the country. When founding the University of Chicago, JDR met Frederick Gates, an ordained Baptist minister who also had a flair for salesmanship. JDR asked Gates to work for him to assist him with his charitable giving. An organizational genius, Gates quickly transformed JDR’s giving and helped him to organize it “as though it were a business.” He discovered that many of the organizations that JDR had been supporting were dubious. As a minister, Gates shared JDR’s strong Christian imperative to engage with society and to help to solve its problems. But Gates had lost his faith and felt that much of what he had been taught, and, in fact, had himself preached, was simply not true. He felt that JDR’s giving to date did not address the underlying social problems with which this country was confronted:

Poverty

Ignorance

Disease

Racism

Gates helped JDR to redirect his giving into a more fundamental kind of charity. This is the beginning of a move toward modern philanthropy.

Addressing Social Issues

Gates convinced JDR to begin creating organizations to address social issues rather than continue to work through other organizations. The Rockefeller University (originally the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, 1890), the General Education Board, the Rockefeller Foundation (founded in 1913) and also JDR personally, began to provide a great deal of money to create and improve medical education in the United States. These efforts produced a number of people who were scientifically trained in a discipline and could actually effect change. It was an extremely important long-term investment and an unusual choice for JDR, who lived a relatively healthy 97 years, favored homeopathy and had no great faith in medicine himself.

Philanthropy’s Unexpected Obstacles

As requests for grants poured into the office, Gates and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (Junior), who had recently graduated from Brown University and begun working in his father’s office, tried repeatedly to refine the system by which they sorted and contemplated the multitude of requests received. When JDR traveled to Europe, he returned with trunks full of letters and requests for financial assistance. Junior and Gates tried to answer every credible request. They soon realized they needed a separate organization to read and answer the letters and to take proper action. By 1910 or so, JDR had $1 billion in assets. Gates famously said to him, “Your wealth is building up, and if you do not make arrangements for it, it is going to overwhelm your descendants. You must do something to organize all of it.”

The increasing volume of requests and JDR’s great wealth led to the creation of the Rockefeller Foundation. The Foundation had very specific programs:

Medical education

Public health

Labor relations in the United States

The Rockefeller Foundation was not met with tremendous popular acclaim at the time. In fact, it was met with the opposite— tremendous suspicion. What are the Rockefellers up to now? This led JDR and Junior to understand that they had to operate the foundation in such a way that it would gain not only the grudging acceptance but also the trust of the American people.

Involving the Next Generation

Recognizing that Junior shared his sense of obligation to engage with society for positive change, JDR transferred approximately $500 million to his son and stepped down from his involvement with all of the major philanthropies. Under the guidance of Junior as chairman from about 1915 until the late 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation began to expand its programs and activities.

Impact

Impact

Many families develop philanthropy programs out of the desire to give back to society in return for their own good fortune. Families successful in business wish to repay the society that helped to generate this success. The first two generations of the Rockefeller family were among the small group of individuals who created modern philanthropy by attempting to deal with the root causes of poverty, disease and ignorance rather than simply ameliorating their symptoms through charity. Current philanthropic programs pursued by family members, such as urban revitalization, youth employment and economic development, benefit various segments of the American population. As reflected in the case studies above, personal life experiences can also impact a family’s philanthropy.

Inter-generational collaboration

Another issue that many philanthropic families face is the distribution of resources over a growing number of children in each successive generation. Unless a family’s fortune continues to grow significantly, children will likely have fewer resources to contribute to philanthropy than their parents did. To have the same impact as earlier generations, families often find that members must collaborate with each other.

Collaboration among groups of siblings, cousins and inlaws can be a great opportunity for sharing values, increasing impact, and developing richer programs. The formation of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (RBF) was the first example of Rockefeller family members sharing their philanthropic resources. The five sons of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., known as the “Brothers” generation, created the foundation before World War II, when they found their individual resources strained, and all were receiving requests for support from the same organizations. They decided to pool their funds designated for giving and to make collective decisions, as a more effective and meaningful way to give. The current programs of the RBF are strategic and reflective of the family’s central values. The New York City program demonstrates the family’s ongoing loyalty to the city, while RBF’s international development programs show the interconnectedness of different nations and cultures.

Personal endeavors

Individual Rockefeller family members also maintain their own funds for personal giving. On a smaller scale, members of David Rockefeller’s family collaborate with each other to manage the DR Fund, from which grants are allocated with active participation by his children and grandchildren. These family members rotate into governance roles of the Fund, which allows them to carry on their family’s tradition of philanthropy and also develop their own personal interest in giving.

About 10 years ago, following some highly successful collaborative projects of the fourth generation (commonly known within the family as the “Cousins”), the young adult members of the fifth generation conducted a poll to identify areas of common interest. The environment and education emerged as the leading issues, and fifth generation family members chose to focus on community gardens in New York City.

Once this focus area was identified, the group operated as a collaborative “foundation.” They requested proposals, conducted site visits, participated in the public policy/advocacy process and made joint funding decisions. The fifth generation’s achievements were honored in the fall of 2004 by New Yorkers for Parks, an advocacy organization in support of open, public spaces.

Ripple effects

The ripple effects of this initiative continue to influence younger Rockefellers. Allison Whipple Rockefeller, an active participant in the community gardens collaborative, established the Cornerstone Parks Fund, which seeks to rehabilitate abandoned gas stations in New York State into parks and community centers that will provide access to educational programs, local crafts and farmers’ markets. More recently, 89 members of the Rockefeller family’s fifth and sixth generations have come together with the intention of sharing their resources and talents in a new initiative. A governing council with rotating teams allows the group to maintain the central values on which they were founded, while allowing new members to develop their interests and have an impact on the organizations they support. In this way, the philanthropic values of the family are carried on to the next generations, allowing family traditions to be reinterpreted. As Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors’ president Melissa Berman states, “values, not views” are passed down through the generations of the Rockefeller family. Each new generation applies the family’s values to their own collaborative philanthropic programs that are personally meaningful.

Combining the talents and skills of many different family members can also help expand grantmaking. Pooling resources allows family members to contribute to more sizable grants, and some of the issues addressed in family collaborations are broad enough to require diverse experience and skills.

Emerging Trend: Venture Philanthropy

The Rockefellers’ entrepreneurial founding of nonprofit organizations has qualities in common with the recent trend of venture philanthropy. In both models, donors examine an issue or trend, commit themselves to effecting change and have a direct hand in the work of the organizations their grants support. But the Rockefeller value of personal investment and interest in the causes they support contrasts with typical venture philanthropists. The Rockefellers place trust in the grantee organization, combined with a personal commitment to be involved in the life of the organization. It is often the personal experience of the donor that has inspired their interest in the first place. Also, while the Rockefeller spirit of entrepreneurship has informed their business practices and their giving, they do not operate their nonprofit organizations as though they were businesses. In philanthropy, it is important to engage both the heart and the mind, and so to become personally involved in thoughtful and reflective giving. The impact and continuity of the Rockefeller family’s philanthropy draws on four important forces:

Thoughtful transmittal of values, including obligation, opportunity, collaboration and personal investment, through family traditions and organized meetings;

Consistent adherence to a long-term perspective that focuses on root causes, understanding the time horizon and balancing patience with accountability;

Genuine confidence in the nonprofit sector to creatively solve problems that neither government nor business can address through strong and sustainable organizations; and

Clear understanding of how organizations thrive, including the role of operating support, governance vs. management and shared decision-making.

These principles and practices, now reaching the seventh generation of Rockefellers, with more than 150 descendants of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., have transformed the landscape of philanthropy over the last century— and form a solid platform for continued innovation in giving.

Case Studies

-

David Rockefeller

David Rockefeller, of the third generation, recalls two personal anecdotes that raised his awareness about the importance of recognizing opportunities to give. As a boy, he traveled with his family to Williamsburg, Virginia, where they visited an early American building undergoing restoration. This smallscale project inspired David’s father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to create Colonial Williamsburg. In another life-shaping childhood experience, his family traveled to France in the 1920s. The family saw the damage that had occurred during World War I, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. decided to provide funds to repair the great monuments of France, including Chartres Cathedral, the Palace of Versailles and Fontainebleau. These philanthropic examples taught David to recognize an immediate need for generosity and to respond with grants that have great meaning because of their connection to personal experience.

-

Peter O’Neill

As part of his involvement in running a capital campaign at International House, Peter O’Neill, a member of the fifth generation of the Rockefeller family, developed his skills as a fundraiser. This new perspective of asking for grants gave O’Neill greater insights into the other side of philanthropy. These skills make O’Neill an especially important asset to his generation group. His experiences also help his family members understand how effective fundraising is central to an organization’s sustainability and success.

-

John D. Rockefeller 3rd

The eldest son of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, JDR 3rd (as he was known) balanced the stewardship of a major philanthropic organization, the Rockefeller Foundation, with an equally strong program of personal philanthropy. As the only brother to pursue philanthropy as his primary interest, he had wide-ranging interests in the arts, education, agricultural development, and in the improvement of U.S. relations with Asia. However, for four decades he focused his work and giving on the danger of excessive global population growth. He believed that lowering population growth to sustainable levels would “improve the quality of people’s lives, and help make it possible for individuals everywhere to develop their full potential.” JDR 3rd pioneered the development of effective contraceptives and sought to implement public policies that would enhance the roles and status of women both in the U.S. and around the world.

-

Laura Chasin

Ms. Chasin, the eldest daughter of Laurance S. Rockefeller and Mary French, is a social worker and family therapist. She is also founder and board chair of the Public Conversations Project (PCP). Founded in 1989 to explore the potential of adapting methods used with families in conflict to disputes in the public arena, PCP has worked worldwide to “promote conversations and relationships among those who have differing values, world views, and positions related to divisive public issues.” PCP aims to reduce the rancor in public squares and promote effective communication within organizations and communities. A notable accomplishment has been a dialogue on abortion among Pro-Life and Pro-Choice Leaders in Boston that PCP has facilitated. After the 1994 fatal shootings at two women’s health clinics in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Governor and the Archdiocese of Boston asked that PCP facilitate an ongoing conversation to prevent further violence. Over the next six years, PCP and Laura Chasin designed and facilitated meetings that encouraged communication and dialogue and helped to protect the safety of participants which, as reported in the Boston Globe, led to a lessening of hate-filled rhetoric and conflict.