What is Impact Investing?

What is Impact Investing?

For many years, philanthropy and investing have been thought of as separate disciplines–one championing social change, the other financial gain. The idea that the two approaches could be integrated in the same deals—in essence, delivering a financial return while doing good—struck most philanthropists and investors as far-fetched.

Not anymore.

Impact investing, which seeks to generate social and/or environmental benefits while delivering a financial return, is expanding as a promising tool for both investors and philanthropists. Some estimates value the current impact investing market at nearly $9 trillion in the U.S. alone.

As the problems societies face become more entrenched and complex, it’s clear that government and philanthropy can’t solve them on their own. A look at the amounts of capital bears this out: in the U.S., philanthropy is approximately $390 billion, government spending is $3.9 trillion, and capital markets (all debt and equity investments) encompass $65 trillion. On a global scale, total investments are estimated at $300 trillion. Thus, a 1% shift in global capital markets towards impact investing–or investments that work toward social good–could cover the estimated outstanding $2.5 trillion annual funding gap to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As this example shows, harnessing capital markets can have a huge societal benefit.

Impact Investments, Defined

Impact investments are defined as investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate social or environmental impact alongside a financial return.

While this definition leaves room for a broad set of investments, two key elements should be present: intentionality and measurement. The investor’s intention should include some element of both social impact and financial return. And while there is more consensus on metrics for financial return on investment (ROI), an impact investor should also aim to measure the social impact. In essence, all investments make an impact on society; some positive, some negative. Impact investors intentionally pursue investments that lead to measured positive social impact (for the purposes of this guide, we include environmental impact in the broader header of social impact).

There are two sides of any impact investing deal: the impact investor and the impact investee. The goal is for both sides to benefit.

Impact Investor: Investments made with the intention to generate measurable social impact alongside a financial return

Impact Investee: A mission-driven organization (for-profit, nonprofit, or hybrid) with a market-based strategy

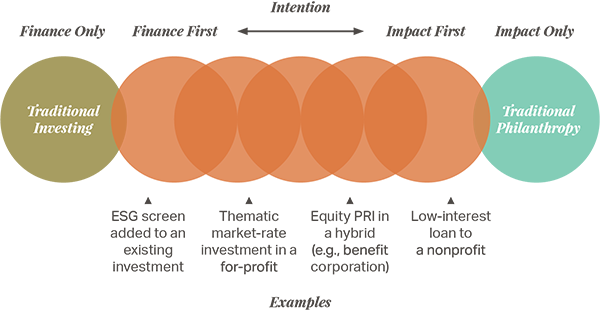

Impact investing appeals to many potential investors because it balances commerce and compassion. It also offers a broad range of options, as shown in the following diagram. Some strategies emphasize financial return while still seeking to benefit society. Other approaches put social impact first, accepting returns that vary from below-market rate to a simple repayment of principal.

Finding one’s place along the spectrum is a key consideration for any impact investor. At the far left, one motivated primarily by social impact might make a low interest loan or recoverable grant to a charity. At the other end, a financially driven approach might lead to an equity investment in a public company based on its integration of corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Impact investments can be as straightforward as banking with a community-based financial institution that helps to expand economic opportunities for low-income stakeholders, or supporting entrepreneurs in the developing world through a micro-finance fund. Some of these types of investment, for example, solar power, have been around for decades.

Impact investments can also be incredibly complex, sometimes creating new financial vehicles or new types of arrangements between partners. These pioneering deals—which could include infusing capital into startup social enterprises, for example, or investing in pay-for-success contracts—often require expert advice, especially for newcomers.

Please note: This guide assumes basic knowledge of philanthropy and grantmaking approaches, as well as financial tools and investment principles. For a review of relevant terms, please refer to the Glossary.

Why Does it Matter?

Why Does Impact Investing Matter?

Regardless of where one lands on the spectrum, impact investing provides a tool for achieving social good with a wider array of assets thana traditional philanthropy. Private foundations in the U.S., for example, can achieve social good with not only their 5% required annual payout, but also with the 95% endowment corpus that remains invested. To put this in perspective, U.S. foundations make annual grants totaling $60 billion, while holding assets totaling $865 billion.

How does impact investing help further impact goals?

- It’s a powerful tool for leveraging philanthropic dollars. Investment returns can be reused over and over again to compound the impact.

- It allows donors greater freedom and flexibility to test innovative ways to achieve a financial return as they seek impact.

- Donors use it to breathe new life into or complement their philanthropic strategy. Many report great satisfaction after incorporating impact investing in a redesign of their approach to social change.

When applied to specific social causes, impact investing also has the potential to bring more capital and fresh approaches to targeted issue areas. For example, efforts are growing to coordinate impact investing with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 15-year global goals that all the world’s governments and many businesses and nonprofits committed themselves to beginning in 2016. The 2017 GIIN Annual Impact Investor Survey found that 60% of investors reported are actively (or soon will be) tracking the financial performance of their investments with respect to the SDGs.

How does impact investing help further financial goals?

- Strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices embraced by many social good projects may lead to financial outperformance.

- Merging investment and impact efforts can streamline strategy and help achieve returns (as well as impact) with larger pools of money.

- Investors can bring market-based approaches to bear on the social causes they care about while avoiding making investments that are in opposition to their values.

How can philanthropy help advance impact investing?

- Philanthropy can pave the way for promising investments that don’t yet attract pure investment capital due to higher risk, an unproven track record, or an uncertain return timeline. In this case, philanthropy can provide risk capital, early capital, or patient capital. One example is a loan guarantee allowing a social enterprise to access credit at a favorable rate.

- For over a century, philanthropy has honed one of—if not the—most challenging aspects of impact investing: impact measurement. Philanthropy can coordinate with impact investors to appropriately evaluate impact, which can then be measured along with the desired financial return.

- Philanthropy can help develop, scale and professionalize the impact investing field through education, training, research and infrastructure building.

Two organizations that highlight the power of philanthropy’s role are the Rockefeller Foundation and the Case Foundation. The Rockefeller Foundation helped shape this space in the mid-2000s, by assembling a group of philanthropists, investors and entrepreneurs that coined the term “impact investing” and by incubating the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), the leading network of practitioners. More recently, the Case Foundation has worked to build the field by creating a primer guide, narrative analytics on how the field is perceived and a network map using transaction data to highlight investment activity and trends.

Where is it Going?

Where is Impact Investing Going?

As individuals and organizations seek new ways to tackle the problems that matter to them, market-based approaches are becoming better understood and more widely practiced. Here are some key indicators of impact investing’s growing influence:

Market Size & Growth

From the US SIF Foundation’s 2016 Report, assets under management that incorporate ESG considerations totaled $ 8.72 trillion—a 33% increase over 2014. These assets now account for more than one out of every five dollars under professional management in the United States.

Foundation Integration

In addition to the use of program-related investments (PRIs), foundations are beginning to invest endowment money for impact as well as financial growth. Many of the world’s largest foundations have pledged a significant portion of their endowments towards impact investing—with the Ford Foundation’s $1 billion commitment being the largest to date.

Going Mainstream

Surveys of high net worth households indicate that achieving social impact is important to over 90% of respondents, with interest set to grow as the millennial generation engages as philanthropists, creating conditions for more experimentation and innovation. Furthermore, 2017 GIIN Survey respondents saw progress in key indicators of industry growth, such as the availability of qualified professionals, data on products and performance, and high-quality investment opportunities.

Institutional Interest

Impact investing has caught the attention of institutional investors, driven by client interest. BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, Bain Capital, and TPG are just a few that have taken significant steps to integrate impact investing into their asset management offerings. Moreover, across the financial industry the number of SRI (socially responsible investing) mutual fund and ETF offerings has grown rapidly over the past few years. MSCI and Morningstar—leading providers of independent investment research—have also released ESG indices and ratings to inform investment decisions.

Government Involvement

Policymakers and government entities have also shown increased interest. At the national level, the U.S. National Advisory Board on Impact Investing provides a framework for federal policy action in support of impact investing. Internationally, the Global Social Impact Investment Steering Group (GSG) was established in 2015 as the successor to the Social Impact Investment Taskforce, established by the G8.

As for regulation, in the U.S. for example, the Treasury and the Department of Labor in 2015 announced favorable rulings and guidance on applying social impact considerations towards investment decisions. Many state and national governments are currently discussing such policy reforms.

Competitive Investment Returns

Numerous studies now point to the competitive nature of impact investment financial returns. For example, a report by Cambridge Associates & GIIN shows that impact investment funds launched between 1998 and 2004—those that are largely realized (converted to cash)—have outperformed funds in a comparable fund universe.

Taxonomy & Impact Measurement

As impact investing gains traction among a wider range of investors, efforts to codify impact measurement have been amplified. A number of relevant frameworks now exist, an example of which is the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS) —an early taxonomy providing the foundation for impact measurement. New accounting standards are also in development by the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB) to track social metrics in public companies.

Pros & Cons of Impact Investing

Benfits & Challenges in Impact Investing

Benefits

Donors and investors say they are attracted to impact investing for a variety of reasons, including:

Return on Investment

In general, an impact investor can reinvest the same money in a series of socially beneficial projects or organizations. Even a simple return of principal creates philanthropic leverage unattainable through traditional grantmaking.

More Assets can be Aligned with Philanthropic Goals

Foundations are required by law to disperse at least 5% of their assets each year in order to achieve charitable goals. The remaining 95% of foundation assets have traditionally been focused on seeking market returns. Impact investing allows more of that philanthropic money to be leveraged for social or environmental change.

Investors Don’t Work Against Themselves

When investments are in line with philanthropic values, donors don’t find themselves in the awkward situation of holding public ownership in companies that conflict with – or even actively undermine—their grantmaking strategy.

Challenges

Donors note that other aspects of impact investing can pose difficulties:

Investments can Carry Significant Risk

As with traditional investments, impact investments come with various levels and types of risk, and it is arguably more ambitious for a company to aim for impact along two dimensions rather than one. For example, some social enterprises seeking impact investment may operate in underdeveloped markets, where a business or nonprofit faces the challenge of helping to create infrastructure as well as provide a service.

Lack of Deal Flow & Strategies

The supply of investment opportunities offering scale, impact and financial return sometimes falls short of demand. As a result, impact investors can experience frustration finding deals that fit both their investment criteria and their philanthropic orientation. Once an investment is made, it can be challenging to find an attractive exit strategy. For example, the first IPO of a benefit corporation only occurred in early 2017. In the international context, when investing in markets with government currency controls, it may be more complicated to get one’s cash back.

Lack of Expertise & Market Fragmentation

Many financial advisors lack expertise in the social aspects of impact investing. At the same time, many philanthropic advisors lack expertise in making financial investments. A new breed of advisors with experience in blending philanthropy and investment (as well as related legal issues), although growing, is only just emerging. Thus it can be difficult to build a team with the requisite expertise in both impact and financial return.

Difficulty of Measurement

While there have been great strides in standards for impact investment performance, coordinating an industry standard of impact measurement has proven difficult. Traditionally, investments and social impact occupied different spheres of life, approaches, and sources of capital, and social impact and assessment approaches are investor-specific. Accordingly, It can be quite challenging to break down these barriers, then decide how to integrate the two.

How are they Structured?

How are Impact Investments Structured?

Impact investments made by foundations and other mission-based organizations to further their philanthropic goals cover two distinct categories:

Mission Related Investments (MRIs): MRIs are risk-adjusted, market-rate investments made as part of a foundation’s endowment and have a positive social impact while contributing to the foundation’s long-term financial stability and growth.

Program Related Investments (PRIs): PRIs are IRS-defined below-market rate investments made by private foundations designed to achieve specific program objectives. As opposed to MRIs, PRIs have a legal definition in the U.S. and count as a qualified distribution towards a foundation’s 5% annual payout requirement. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, uses PRIs to complement its traditional grantmaking and to scale social enterprises that serve the poor.

In addition to the distinction for foundations between MRIs and PRIs, the following categories will shape and be shaped by an investor’s specific approach to impact investing.

Investor Structure

While the foundation structure has been the philanthropic vehicle of choice since 1969, the last 10 years have seen innovative structures arise to match impact goals with available opportunities. Models utilizing LLCs, DAFs, private foundations and public charities, for example, have disrupted the traditional approach. For example, Laurene Powell Jobs was an early adopter of the LLC as her primary vehicle in running the Emerson Collective. More recently, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has implemented a combination of LLC, DAF, private foundation, and 501(c)(4) structures —forgoing tax benefits to optimize flexibility and maximize impact. For more information on how to structure your philanthropy, you may find RPA’s guide Operating for Impact a helpful resource.

Investee Structure

A new world is developing in which both for-profit companies and nonprofit organizations can be values-driven and market-responsive. More and more nonprofits are generating revenue through the sale of products or services, while for-profit companies are integrating social good into their business models.

To keep pace with these blended corporate aims, hybrid corporate forms have developed. For example, since the organization B Lab began its work in 2006, 33 states have enacted legislation for incorporation as a “benefit corporation,” in which a company prioritizes public benefit over financial performance. In addition, over 2,000 organizations in over 50 countries have taken up a non-legal designation of B Corporation that have been vetted to account for the company’s social purpose.

Investment Structure

The structure of the transfer of money itself also has a range of possibilities. The investment structure can incorporate cash, private and public debt or equity, real assets, or other innovative instruments—such as pay-for-success contracts. Of these options, the 2017 GIIN Annual Survey shows private debt as the most common investment structure.

Is Impact Investing a Good Fit for You?

Is Impact Investing a Good Fit for You?

Whether impact investing is a strategy you should consider will depend on your values and goals, and on how well you understand the opportunities before you.

Impact investing can be daunting because it requires both financial acumen and philanthropic issue knowledge—a rare combination, not to mention unique human resources and legal considerations.

Yet, the field offers great potential.

Virtually any philanthropic issue has an impact investment opportunity associated with it, and virtually every asset class used in a traditional investment portfolio has an impact equivalent. In an age when social entrepreneurs, technology and connectivity have redefined the potential to improve people’s lives, impact investing seems an ideal vehicle for linking the power of markets with the passion to do good.

One key concept to remember: impact investing is one tool of many to achieve your goals. First, determine what success might look like, then work backwards to determine how you might integrate impact investing into your overall portfolio. From the GIIN’s 2017 Annual Impact Investor Survey: “While two out of three respondents principally target risk-adjusted, market rates of return, there is widespread acknowledgement of the important role played by below-market-rate-seeking capital in the market.”

“The Ford Foundation’s approach has unique value to add with $1B of assets committed, while our [Surdna Foundation’s] approach has particular influence with $100M committed…the key is to view impact investing as one of many tools…we need all different approaches to realize the fullness of what impact investing has to offer.” - Shuaib A. Siddiqui, Director of Impact Investing, Surdna Foundation

Moving Forward

Moving Forward

To consider the next steps in taking action towards impact investing strategy and implementation, please refer to the accompanying guide, Impact Investing: Strategy and Action, which will explore how to prepare for, build, and refine your approach to impact investing.

Case Studies

-

Creative Support for New Communities

Wachs Family Fund

As a philanthropic tool, impact investing can help even experienced donors discover new ways to help the organizations and causes they care about. For the Wachs Family Fund, a donor-advised fund (DAF), it offered the flexibility to experiment—and a source of tailored support for a complex problem.

Elizabeth Wachs, who created the DAF, had a longstanding grant relationship with Communities Unlimited (CU), an organization focused on colonias—communities of low-income individuals, often migrant workers, who live at the fringes of incorporated areas in south Texas. Colonias are often the first landing ground for immigrants in the state, particularly those from Mexico. They lack services or utilities, and their residents often occupy improvised housing.

CU began their work in the colonias with access to clean water after a cholera outbreak in south Texas, which brought their attention to the rent-to-own schemes that put homeowners in a disparate position of power relative to developers. Ownership of the land in these communities can be complicated; harsh penalties within many homeowners’ agreements often resulted in land loss and instability. When the owner of one colonia defaulted on his loan and land ownership transferred to the bank, the Texas Attorney General approached CU and asked if they were willing to receive the property after bankruptcy and redevelop it. CU, enthusiastic about delivering clear titles to the people who lived there, said yes. As the last of the affordable land in this region, colonias provide an important path to stabilizing communities. Families wanted to stay for generations, but had trouble affording it, even with a steady income. CU began building model homes and locating financing for low-income community members.

The Wachs Family Fund had been giving unrestricted grants to CU before these developments, which helped with home repair or title adjudication. Elizabeth also became engaged with CU on a personal level, gaining a deep understanding of their work. After plans for redeveloping the colonias materialized, she met with CU’s executive team and asked them what would really help push their work forward. Their answer: being able to control tracts of land and build affordable housing, which was clearly an expensive endeavor. CU brought up the idea of a loan. At first, the possibilities were unclear as Elizabeth wasn’t sure if she could make this kind of transaction through a DAF. But, during a dip in the financial markets and at a time when a $1 million grant wasn’t a viable option, the idea made sense as a way to mitigate some of the risk of a grant and still make a crucial difference for CU’s time-sensitive work. With the help of her advisors, Elizabeth was able to structure a $1 million program loan (distinct from a PRI, which is an option reserved for foundations) that acted as CU’s land bank, structured at 1% interest over seven years. CU used these funds to leverage other institutional lenders and began to control parcels of land, cycling through the process of building, attracting buyers, securing financing, and extracting themselves. The Fund continued to make concurrent grants, helping with organizational development and construction.

Of course, the loan still carried uncertainty. Elizabeth’s trust in CU’s leadership, and the values of the organization, helped lay the groundwork for a new way of working together. She also leaned on the expertise of her advisors, who had lending experience.

In the end, the loan was effective: it offered key bridge financing to help CU approach institutional lenders, and the organization repaid the fund successfully. Within the colonias, small construction firms grew to support the new building efforts. And, as CU moved forward, it became more comfortable in market-based approaches to meeting the needs of its communities.

This example demonstrates several opportunities and challenges of impact investing:

- At even a low 1% interest rate, the Wachs family’s ROI was much greater than they could have attained through grantmaking alone.

- The loan helped CU attract financing from established lenders.

- The donor’s history with CU, as well as a deep understanding of programmatic systems and priorities, fostered trust and reduced the risk that making a loan to a small, relatively inexperienced organization might otherwise have.

- Although this new structure was a bit daunting and took far more effort than would have been necessary for a grant, having an advisory team well-versed in both philanthropy and investing was very beneficial.

The CU loan is an example of how a philanthropic lens can make lending even more powerful. In fact, Elizabeth felt that her impact investment was a highlight of her giving experience and even today, the Wachs family continues to view this kind of loan as one of many tools in their toolbox.

-

Harnessing Markets to Scale Change

Omidyar Network

Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, and his wife Pam believe that the power of markets can “create opportunity for people to improve their lives.” That’s why they started a “philanthropic investment firm,” the Omidyar Network (ON), in 2004.

Every year, they forego millions of dollars in potential tax deductions to be able to combine grantmaking and investment outside the normal umbrella of a foundation.

Why?

Through the experience of building eBay, they discovered the potential of unleashing market forces for good. They believe that scaling innovative organizations can be the best way to achieve impact – and that scale can and should be attained through multiple pathways. This means that their social impact activities operate through both nonprofit and for-profit means. ON’s organizational structure allows it to practice traditional philanthropy, make investments in worthy companies for a return, and influence policies that affect the enabling conditions for its grantees and investees to thrive – for example, encouraging laws allowing charitable tax deductions, or engaging in policy discussions about interest rates for microfinance institutions. These interrelated goals reflect ON’s strategic intent: to create systemic change.

In 2013, the Omidyar Network applied the strategy when it invested in MicroEnsure, which provides health, life, crop and other kinds of insurance products to low-income clients in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. Most of these clients didn’t have insurance before.

MicroEnsure began as a nonprofit wing of Opportunity International, and Omidyar supported the effort with traditional grants. Over time, as the enterprise matured, it became clear that there was sufficient scope to spin it out as a commercial entity – an exciting, if potentially complex, process.

To support that process, the Omidyar Network provided bridge funding – a low-interest loan that offered MicroEnsure flexibility and time to put all the pieces together to make the transition into a commercial venture.

That loan then converted to equity as the Omidyar Network and the International Finance Corporation (a part of the World Bank Group) partnered to make a $5 million investment to spur MicroEnsure’s growth. At the same time, MicroEnsure launched a new joint venture with giant mobile provider Telenor in order to offer MicroEnsure’s low-cost, mobile-friendly insurance products to more than 149 million Telenor clients in Asia and Eastern Europe. With MicroEnsure’s four million customer base at the time of the deal, the opportunity for increased impact was clear.

MicroEnsure’s transition was a “welcome evolution,” according to colleagues at Omidyar, one that will provide “millions of consumers … and their families a critical safety net over the long-term.” The Omidyar Network remains deeply engaged in the ongoing work of the company, providing human capital in addition to financial investment.

Omidyar’s involvement with MicroEnsure demonstrates the continuum of capital that can be applied to nurture an idea, bring it to scale, bridge gaps, and transform it into a sustainable, commercially funded venture that has a positive social impact.

“It’s a small price to pay to be able to use the power of the private sector to improve people’s lives on a very large scale.”

–Pierre Omidyar, on the decision to forgo tax deductions to maximize impact

Resources & Glossary

Resources

Here are additional resources for your impact investing journey.

B Lab, bcorporation.net

A nonprofit organization focused on using business for good through its B Corporation certification, promoting new mission-aligned corporate forms, and providing analytics for measuring what matters.

Confluence Philanthropy, confluencephilanthropy.org

A non-profit network of over 200 foundations that builds capacity and provides technical assistance to enhance the ability to align the management of assets with organizational mission to promote environmental sustainability and social justice.

Global Impact Investing Network, thegiin.org (Knowledge Center: thegiin.org/knowledge-center)

A network of impact investing professionals advancing the impact investing industry and offering information and resources to investors, including a global directory of impact investing funds (ImpactBase), a set of metrics to measure and describe social, environmental and financial performance (IRIS), an annual survey of impact investing trends, and a rating system for impact investing funds using B Lab methodology (GIIRS).

ImpactBase, impactbase.org

A searchable online database of impact investing funds and products, helping connect investors with investment opportunities.

ImpactAssets, impactassets.org

A nonprofit financial services firm dedicated to advancing the field of impact investing, publishing an annual database of 50 experienced private debt and equity impact investment fund managers.

Investors Circle, investorscircle.net

An early-stage impact investor network made up of individual angel investors, professional venture capitalists, foundation trustees and officers and family office representatives.

Mission Investors Exchange, missioninvestors.org

Network of foundations and mission investing organizations offering workshops, webinars and a library of reports, guides, case studies and investment policy templates – with the goal of sharing tools, ideas and experiences to improve the field

The ImPact, theimpact.org (Knowledge Library: theimpact.org/#resources)

A network of families joined by a pact to improve the impact of their investments – providing education, inspiration, and tools to make more impact investments more effectively.

Toniic, toniic.com

An international impact investor network promoting a sustainable global economy and offering peer-to-peer opportunities to share, learn, co-invest – including a searchable directory of impact investments, an impact portfolio tool, and multi-year studies of impact investing portfolios.

UN PRI, unpri.org

An international network seeking to understand the investment implications of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors and to support its investor signatories as they incorporate these factors into their investment and ownership decisions.

US SIF, ussif.org

The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment is aimed at shifting investment practices towards sustainability across all asset classes.

Glossary

Glossary

(Source: Mission Investors Glossary, unless otherwise noted)

Benefit Corporation: A benefit corporation is a new class of corporation that voluntarily meets higher standards of corporate purpose, accountability and transparency. A benefit corporation has a corporate purpose to create a material positive impact on society and the environment; to consider the impact of its decisions, not only on shareholders, but also on workers, community and the environment; and to report annually on its overall social and environmental performance against a third party standard. Benefit corporation language has been passed in at least 22 states.

Blended value: A business model that combines a revenue-generating business with a component which generates social-value; coined by Jed Emerson and sometimes used interchangeably with triple bottom line and social enterprise; sometimes referred to as blended return or blended finance.

Concessionary return: Return on an investment that sacrifices some financial gain to achieve a social benefit (Source: SSIR).

Corporate social responsibility (CSR): A form of corporate self-regulation integrated into a business model; CSR policy functions as a built-in, self-regulating mechanism whereby a business monitors and ensures its active compliance with the spirit of the law, ethical standards, and international norms, and sometimes goes beyond to support or achieve social good (Also referred to as corporate conscience, corporate citizenship, social performance, or sustainable responsible business).

Double/Triple bottom line (DBL/TBL): Investments that deliver financial returns and social and/or environmental impact.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG): Factors which social investors may consider as part of their investment analysis as a way to evaluate whether their investments promote sustainable, fair and effective practices and mitigate potential risks; ESG may be referred to as “ESG investments” or “responsible investing.”

Market rate impact investment: An investment designed to result in positive social or environmental benefits while generating financial returns that are comparable to similar conventional instruments.

Mission-related investments (MRIs): Investments from a foundation’s endowment that seek to achieve specific goals to advance the foundation’s mission while targeting market-rate financial returns comparable to similar non-mission focused investments. MRIs are not an official IRS designation and are conventionally distinguished through the explicit advancing of the foundation’s mission and programmatic goals. Opportunities for MRIs exist across asset classes and issue areas.

Negative screen: Avoiding investments in generally traded companies on perceived social harm.

Pay-for-success contract (Social impact bonds): A contracts that allow the public sector to commission social programs and only pay for them if the programs are successful.

Program-related investments (PRIs): Investments that provide (1) capital at below-market terms or (2) guarantees to non-profit or for-profit enterprises whose efforts advance the investing foundation’s mission; PRIs are counted as part of a foundation’s annual 5% distribution requirement; generally expected to be repaid, they can then be recycled into new charitable investments, increasing the leverage of the foundation’s distributions.

ROI: A performance measure used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment or to compare the efficiency of a number of different investments. ROI measures the amount of return on an investment relative to the investment’s cost. To calculate ROI, the benefit (or return) of an investment is divided by the cost of the investment, and the result is expressed as a percentage or a ratio (Source: Investopedia).

Social enterprise: An organization that applies commercial strategies to maximize improvements in human and environmental well-being, rather than simply maximizing profits for external shareholders; can be structured as a for-profit, non-profit, or hybrid.

Social entrepreneurship: The process of pursuing innovative market-based solutions to social problems while adopting a mission to create and sustain social value.

Social finance: An approach to managing money that delivers a social dividend and an economic return.

Socially responsible investing (SRI): An investment strategy that seeks to consider both financial return and social good; socially responsible investors encourage corporate practices that promote environmental stewardship, consumer protection, human rights, and diversity; also known as sustainable, socially conscious, “green” or ethical investing.