Moving From Intent to Action

Moving From Intent to Action

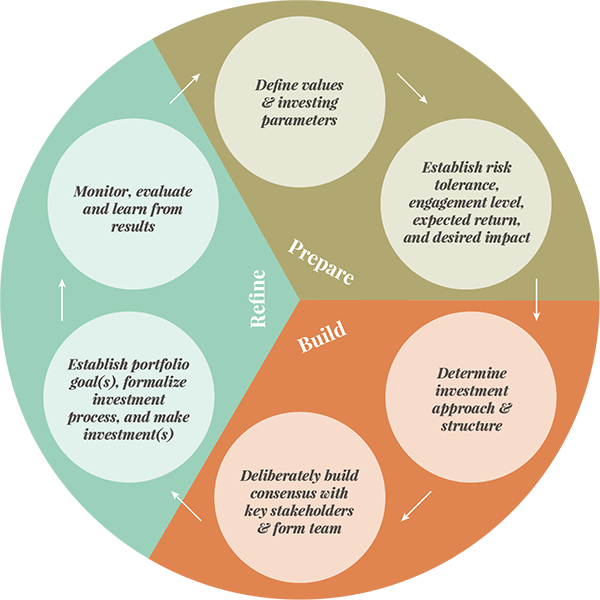

Developing an impact investing strategy and taking subsequent action steps can be organized into three stages: PREPARE, BUILD, and REFINE. We explore each of these phases in detail in this guide.

Please note: this guide builds from the introductory guide Impact Investing: An Introduction, and assumes basic knowledge of philanthropy and grantmaking approaches, as well as financial tools and investment principles. For a review of relevant terms, please refer to the Glossary.

Stage One: Prepare

Stage One: Prepare

As you prepare for your first investment, it’s important to clarify the motivations that will guide your work. The overarching question is “What do you wish to achieve?” To arrive at an answer, we suggest exploring five key considerations: Why, What, How, When, and Who.

Note: If you’re interested in some deeper introspection around your overall philanthropic vision, we recommend our Philanthropy Roadmap guide.

Why?

Why are you interested in impact investing? Your answer could contain one or more of the responses below.

Social Impact

Those focused primarily on social impact may be motivated by heritage, family, faith, or legacy considerations.

Integration

Some investors no longer want to wear two separate hats for investing and philanthropy, and are drawn to impact investing to do both as complementary strategies.

Innovation

Often focused on social entrepreneurs, impact investors driven by innovation look to new and adaptive technology and other promising ideas to make a difference.

Sustainability

Those pursuing impact place a priority on organizations with operating models that have the potential to be self-sustaining.

Market-Based Approaches

Many impact investors are attracted to the power of market forces to create social good.

Analysis

Investors driven by analysis often emphasize data in order to bring an objective lens to address significant needs, optimizing potential impact and/or financial return.

Scope of Impact

Compared to the smaller size of philanthropic capital, the scope of capital markets introduces a huge pool of money to be leveraged for good. For foundations, the 95% endowment can be used for impact in addition to the 5% annual payout.

Investment Performance

Investors prioritizing investment returns will focus on impact considerations that lead to financial outperformance.

Of these, what values and considerations do you hope to reflect in your impact investing?

What?

What kind of change do you want to create through your impact investments?

Big Challenges

Broad categories include poverty, health, education and climate change.

Specific Challenges

Most impact investors will drill down to further define their focus. For instance, someone interested in education might look closely at companies delivering innovative educational technology.

Populations

Some impact investors will concentrate their support on a specific type of community—including women, children, the elderly, youth,

or refugees.

Places

Place-based investors are often driven by heritage or experience, funding many different issues within a geography—a continent or region, a village or neighborhood.

Institutions

Other investors look to support organizations that achieve the goals they care about, including advocacy organizations, arts organizations, charter schools or other academic institutions.

Innovative Solutions

Investors driven by innovation seek new technologies or approaches that disrupt existing models to solve social problems.

General Good

Often focusing on financial returns, some investors are less focused on one social issue or specific challenge but wants to see good done as a result of their investments.

Investment Performance

Still other investors want to see strong risk-adjusted financial returns, placing less priority on the resulting social impact.

Of these, what problems, fields, or approaches are the most compelling to you and what might success look like?

How?

How will you assess your progress? This section focuses on measurement, while additional HOW considerations are explored in the BUILD stage.

Touching on both core aspects of the definition of impact investing —intentionality and measurement—impact investors should develop an approach to evaluating performance on both the financial and the social sides of their investments. Unfortunately, some neglect this process and wait until after an investment has been made to consider how to evaluate it. Thinking of this upfront will shape not only your evaluation framework but also your investment selection and broader strategy.

Measuring Social Impact

There are numerous reasons to evaluate the social impact of an impact investment. Here are three important ones to consider:

- Accountability: Make sure the investee does what it said it would do

- Decision making: Informing future investment decisions

- Proof of concept: Paving the way for larger, institutional capital

At what level do you hope to measure?

Impact assessment can be focused on many levels, from returns on individual investments to impact on general society. The diagram below lays out the possible layers of evaluation—with both a social and investment lens.

The more you move towards the outer circles, the more time and resources you’ll need to evaluate the impact your investments

have achieved.

As mentioned in the introductory guide, impact measurement can be one of the most challenging aspects of impact investing, so be patient and realistic with your expectations.

Financial Returns

What is your desired return on investment (ROI)?

Just as we saw with impact measurement, there are levels of focus that inform how you’ll measure ROI. For more information on impact evaluation, see our “Assessing Impact” guide. A resource with a focus on assessing impact investments, such as the Rockefeller Foundation’s report “Situating the Next Generation of Impact Measurement and Evaluation for Impact Investing” may also be helpful.

What is your appetite for risk?

When thinking about your desired financial and social ROI, it’s helpful to consider your appetite for risk. A common framework to judge the viability of an investment is the balance between risk and return. Within impact investing, that risk applies not only to financial returns, but also to social impact. For example, you may be interested in investing in efficient cold storage to deliver vaccines to rural communities. Funding new, promising technology could have the potential of high social impact, yet also carries high impact risk should the technology fail. In addition to failures, downside impact risk can come in the form of opportunity cost as well as unintended negative effects.

When applied to impact, how much risk are you willing to take to reach your impact goals?

When applied to financial returns, how much risk are you willing to take to reach your target ROI?

In family foundations or collaborative funds with multiple donors, be mindful not only of individual risk appetite but also collective risk appetite.

When?

Effective investing relies not only on how to invest, but also for how long. Impact investments with a higher tolerance for risk often lead to longer time horizons.

As you consider potential investments, the question of when takes two forms:

- What is your desired time horizon for social change to happen?

- What is your desired investment timeline for your financial return?

Keep in mind that investment time horizons are often shorter than impact time horizons.

Who?

Regardless of your impact investing philosophy, you will be working in concert with others on some level. Deciding who to involve, and how, is essential to your success and growth as an investor.

How deeply will you engage with your investments?

Some impact investors wish to work closely with the organizations they support, while others find this less appealing. Your available time and energy could impact key decisions, such as the use of direct investments or funds. It will also influence your choice of professional advisors.

Who else will be involved?

Take some time to consider who else might be important to this process. This could include family members, investment or social change advisors, and board members. The BUILD stage below will tackle how to best engage these other parties.

Who can you partner with and learn from?

While some impact investing is straightforward, many investment opportunities can present tax challenges and legal hurdles. Professional advice from legal, financial and philanthropic perspectives is critical, especially when considering direct investment.

In addition to professional advisors, consider which peers you admire in this work. Begin to think through ways to build a relationship with them, learn from them, and potentially partner with them. As this field matures, many peer learning networks will present similar opportunities; while some impact investors prioritize transparency (e.g., Heron) and others have a mandate to share learnings (e.g., Omidyar Network).

Once you’ve put ample time and thought into the PREPARE stage, you can move into the BUILD stage, gearing up to make an investment.

Stage Two: Build

Stage Two: Build

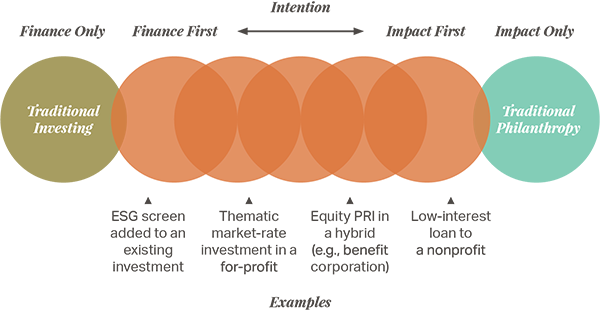

Where do you land on the impact investing spectrum?

As presented in “Impact Investing: An Introduction,” the following spectrum presents one way to consider your approach to impact investing. For example, if you land on the far left (prioritizing financial return), your approach will be quite different than if you land on the far right (prioritizing social impact).

As you see the balance between impact and financial return, what part of the spectrum are you drawn towards? Which one reflects your desired approach?

Before moving forward, it’s important to add the consideration of two additional variables: level of engagement and risk tolerance. We reviewed these lenses separately in the PREPARE section; it’s now time to put them together with specific investment ideas and examples.

Lower Risk / Low Engagement

Community Financial Institutions

This approach can be as easy as opening an account with an institution that focuses on lending in low-income, disadvantaged communities. Working with an organization like this takes little effort on your part. There are thousands of these entities in the U.S.; one particular type is called a CDFI, or community development financial institution, which finances community businesses in difficult-to-serve markets across the U.S.

Special Purpose Funds

These intermediary organizations usually accept charitable funds from donors, then convert them into equity investments, loans and guarantees in social enterprises. Benefits include the adjusted risk derived from being part of a large pool of investors. Disadvantages include limited investor control over implementation.

Variable Risk / Low Engagement

Established Microfinance

Organizations such as Accion and Blue Orchard offer impact investors a relatively simple way to support entrepreneurs and their small businesses. Risk is dependent on the entrepreneur, but the microfinance umbrella organizations and their affiliates conduct due diligence and monitor loan performance.

Impact Investing Funds

These private equity and debt funds make a range of investments seeking positive social and environmental impact and a financial return. The nonprofit ImpactAssets offers a guide to impact investment fund managers, and the Global Impact Investing Network, has a searchable database of impact investment funds called ImpactBase.

Lower Risk / High Engagement

Shareholder Activism

Investors may use their equity stake in a company to attempt to influence its management and policies. The attempt to integrate social values into investor action can apply to corporate social responsibility or specific issue areas. Investors can work individually or in coalition with others, pushing to influence corporate behavior from within.

Variable Risk / High Engagement

Program Related Investments (PRIs)

By law, these investments are only open to private foundations. PRIs are often loans, loan guarantees, deposits or equity investments. The primary purpose of the investment must be accomplishing part of the foundation’s mission. Unlike grants, PRIs are expected to be paid back, often with a modest rate of return.

Direct Investment

Some philanthropists go to great lengths to set up their own deals. They may want to invest in the project of a social entrepreneur, acknowledging the risk that can come with a promising but potentially untested idea and a new organization. Ideally philanthropic investors save the cost of their own due diligence by sharing it with others. Root Capital, a hybrid social enterprise, provides shared due diligence to investors, who agree to receive one shared performance report. This allows the investee to devote more resources to innovation, R&D and growth. Nonetheless, direct investing can carry more risk than investing in funds.

Quasi-Equity Debt

This innovative instrument is a loan with equity characteristics–often used to mimic an equity investment in a nonprofit (a true equity investment in a nonprofit is not possible). The equity-like returns are generated by indexing payments to the organization’s financial performance. Investors often like this structure as a way to incentivize the investee to operate efficiently.

High Risk / High Engagement

Pay For Success (Social Impact Bonds)

Pay for Success projects, also known as social impact bonds, are contracts that allow the public sector to commission social programs and only pay for them if the programs are successful. These contracts also rely on private investment, which only earns a return if the social programs achieve their goals. Social impact bonds can leverage social change and earn a financial return. Risk is often high.

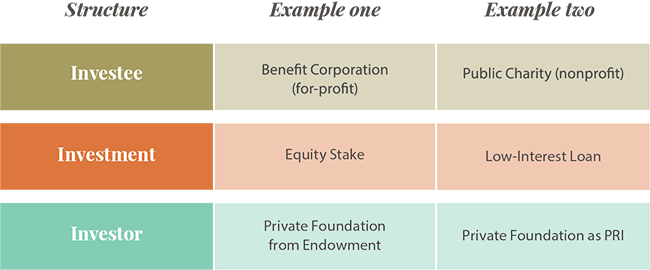

Structure

While navigating these four variables (risk, engagement, impact, and return), one key consideration relates to structure. Here we will review the different structural options as detailed in the first guide.

Size

The size of the investment should match the investee size and needs. In general, larger investments will lead to higher risk and higher engagement as well as higher potential return and impact.

Investee

Depending on your approach, you will likely look for different investee structures, though different structures can sometimes carry out similar goals. You might choose a charity, a benefit corporation, or a public company.

Investment

As you continue to hone your goals and investment specifics, the investment structure plays an important role. It should be an appropriate choice for the investment size and investee structure. You might choose a loan or a direct equity investment to achieve your goals.

Investor

Given your goals and existing charitable vehicles, you may choose to make your investment out of a non-charitable vehicle, a donor-advised fund, a private foundation, or another vehicle. For a private foundation, you might prefer to start with a PRI from the program budget or a MRI from the endowment.

To be clear, structure decisions affect each other. Two possible extremes might play out in the manner depicted below.

Build Consensus

Unless you’re acting alone, impact investing can be as much about organizational change or interpersonal dynamics as it is about investment selection. Introducing the concept to a group of collaborators has proven to be difficult for many, given the range of priorities and understanding within a foundation, family office or family.

For more specific considerations, please also see our guide “Talking with Your Family about Philanthropy.”

Keep the four variables (Impact, Return, Risk, and Engagement) in mind as you engage key actors towards impact investing implementation. Strategies to keep in mind that may aid in building consensus include the following:

- Look for easy wins, especially at the beginning.

- Meet each individual where they are. Find out their values, risk-tolerance and biases, then be ready to speak—in their language—to their particular excitements and/or concerns.

- Leverage advocates and partners to support you and champion the cause.

- Consider presenting impact investing as one of many tools to achieve the organization’s goals.

- Consider how to merge the often-separated finance and impact considerations, aligning impact goals with financial ones.

- Find appropriate anchors for the conversation. For example, a 50% return of capital would be considered a bad investment, yet could be quite the compelling grant.

- Come to the table with data and success stories. For example, a growing body of analytics points to competitive financial returns for impact investments.2

- Start from a place of strength: consider a loan to an existing grantee that you know well, or an ESG screen for the next investment in a familiar sector or asset class.

- As you begin building consensus, recognize that this will be an ongoing process of informing, educating, and responding to key stakeholders. This is true for even seasoned impact investors. The Michael and Susan Dell Foundation (MSDF) have helped lead impact investing in India for over 10 years. In recent efforts to apply this tool to their U.S. education work, it has taken thoughtful education and communication from program officers and impact investing staff to begin implementation.

Choose the Right Advisors

One important way to build consensus is to choose advisors that make everyone feel the most comfortable. Picking the right advisor can make or break the implementation of impact investing.

Here are a few guiding principles for choosing the right advisor

for you:

- Do they have expertise at the intersection of your four variables above? For example, do the rigor and expectations with which they approach impact evaluation match yours?

- Do they have specific examples of their experience and the role they played in investments that relate to your desired impact?

- Do they have credentials to satisfy the work requirement AND to satisfy all or most of your key stakeholders?

- Can they speak your language and help you reach your unique goal

Alternatives to working with advisors are learning from well-informed peers, joining relevant networks, and learning from industry publications and training.

Formalize Your Team

As you build consensus and consider advisors, also reflect on who might join your formal, ongoing impact investment team, if applicable. Think of those who have significant internal or external influence as well as those with particular social impact and/or investment expertise. For example, a private foundation might create a balanced committee with both program and investment staff working together. Look for characteristics particularly helpful to the task at hand, including flexibility, collaboration, patience, analytics, and diversity.

Stage Three: Refine

Stage Three: Refine

Make Your First Investment

Start From Strength

If you know a charity well, and they already have a revenue generation dimension to their operations, you may want to start with a loan to that charity to supplement your grants. If your foundation has strong investment talent, you might start with financial due diligence of potential opportunities. If you are coming from an investment angle, you might slowly integrate an ESG consideration to a portion of public equity holdings.

Coordinate With Philanthropy

On the impact side, we recommend—where possible—aligning impact goals for both philanthropy and investing. Consider reviewing your current and potential portfolio for philanthropy challenges that might be better served by an investment than a grant, such as, for instance, a low-interest loan to a nonprofit that wants to purchase office space.

When you feel comfortable with your progress towards your first investment, focus on one or a small set of investment opportunities. Review what you have covered in the PREPARE and BUILD stages to confirm adequate alignment. When you’re ready and all the key stakeholders are informed, go for it!

This stage reflects the important iterative approach as seen in the Impact Investing Implementation Cycle diagram. Many of the above considerations depend in each other, so it’s important to review your choices and actions continually, especially early in the process.

Formalize Your Structure

As you start making investments, consider the best investor structure to accomplish your goals. This structure should match closely with your operational resources, as well as your desired investee and investment structure. Pay attention to find the right balance of complexity, flexibility, and resources required. For more details on operating models, please refer to RPA’s Operating for Impact guide.

Formalize Your Process

Create an Investment Policy Statement that reflects your approach, alongside adjustments to other relevant investment or grant procedures. Begin to also formalize investment decision making parameters, including how to monitor and evaluate current and prospective investments—including when to cut your losses and walk away from an investment.

Formalize Your Systems

Assess your systems to be sure that they map well to your desired impact investing approach. See the Resources in the appendix for investment databases and affiliate groups that might help inform your systems.

Define Detailed Goals

As you become more comfortable with individual investments, begin to shape one overarching goal that drives your impact investing strategy. Examples of this could include picking one particular challenge and addressing it from all angles, or carving out a percentage of assets to put towards impact investing. Some organizations, like Heron, have been so bold as to commit 100% of assets towards impact.

Consider Multiple Structures and Approaches

Once you have a handle on one approach, you may want to revisit the PREPARE and BUILD sections to add a second approach. For example, if you started with PRIs, perhaps your second approach could use a portion of your endowment to invest directly in social enterprises.

Then What?

Once you’ve reached your initial goals, you can begin thinking of how to advance the field overall. Some ideas include:

- Leading content creation through publications, interviews, and conferences

- Helping build market infrastructure, like SASB accounting efforts

- Training and educating

- Convening others and helping build broader interest in impact investing as a tool for philanthropists and investors

- Advancing the practice of measuring of social impact alongside financial return

As you grow, remember that you can be a source of encouragement and knowledge for others.

Case Studies

-

Both Sides of the Coin

The Aragona Family Foundation

What happens when due diligence yields new information that changes the nature of an impact investing deal? As the Aragona Family Foundation (AFF) discovered, the inherent flexibility of the practice can offer more than one opportunity for positive social impact, even with surprises. And when that happens, the know-how of foundation staff is critical for success.

AFF is a family foundation headquartered in Austin, Texas that focuses on local issues including healthcare navigation, educational attainment, workforce development, and social innovation/entrepreneurship. Chris Earthman, who runs the foundation’s investments and giving, brings a mix of knowledge and skills to his role. His background includes both traditional investing and nonprofit experience, which gives him a unique blend of expertise to implement impact investing at AFF. The Foundation’s experience with impact investing began with a recapitalization event in the fall of 2014, leading the trustees to set aside a portion of newly contributed assets to “test” the local market for impact deals that aligned with the foundation’s giving criteria. Chris had been following impact investing trends and studying successful deals for several years prior to this experiment, a precedent which helped AFF evaluate its investment criteria and take action when an unusual opportunity came their way.

Chris and the team at AFF began due diligence for an investment in Student Loan Genius, a social enterprise that was providing student loan benefits and has since expanded to focus on financial wellness and engage consumers who face student loans. The team entered the conversation expecting to make a Program Related Investment (PRI), where the social benefit to students outweighed the prospects of a financial return. Chris initially believed that one of the primary proof points for charitability in this PRI was the lack of commercial investors due to the early-stage nature of the investment. However, during their due diligence, AFF learned of new and significant interest from a large strategic investor who had negotiated terms for a new round of financing. This realization, while not a deal killer, began to tip the balance in AFF’s mind towards financial return, where the Foundation found it harder to argue that the social benefits outweighed the financial ones.

Familiarity with the flexible nature of MRI vs. PRI-level charitability available to private foundations led to a different conversation: if the Aragona team had the ability to invest in a company that clearly supported one of their impact verticals, did it matter what vehicle they used? The answer turned out to be “no.” As the deal moved forward, Aragona sought advice from local experts including their nonprofit attorney and other individual investors in the company. With the increased clarity, Chris and the AFF team decided to make an MRI, rather than a PRI—an unusual decision mid-process. Chris points out that, “If you’re worried about proving charitability as the IRS defines it, you can still look for impact-driven deals that can be served with an MRI. For small-staffed foundations like ours, I love the flexibility that this toggle can provide.”

Along the way, Chris incorporated some helpful practices to engage the foundation’s risk aversion and build consensus:

- As the impact investing community in Austin grew, he identified local intermediaries for deal sourcing and shared due diligence—often investing through a syndicate.

- He provided audience-specific financial and impact reporting to keep trustees and other stakeholders apprised of which deals were successful and how. Just as importantly, he kept his trustees apprised of deals he screened out of consideration and why.

- He leaned on his passion, skills, and mission-alignment when seeking buy-in from trustees.

He started small, with loans to nonprofits offering structured returns with some level of collateral. - He positioned impact investments with his trustees as an additional tool to improve upon traditional grants by incorporating the possibility for a financial return alongside the social impact.

So far, Aragona has made six investments at a range of positions on the impact/return spectrum while using traditional loans, convertible debt, and preferred equity. The implementation of these deals have been made possible through the Foundation’s expertise, flexibility, responsiveness, and thoughtful collaboration, proving one viable entry point into impact investing. That said, the conversation is still quite early regarding the extent to which AFF will adopt further impact investments.

A larger scale adoption will take a steady approach of stakeholder education, consensus building, and risk monitoring.

“If nothing else, I’d like folks to know that impact investing is not exclusively a tool or domain for the large multi-billion dollar national foundations. In our case, a local family foundationwith part-time staff and modest giving budget was able to engage directly in impact investing locally as one additional tool in our consideration set.”

-Chris Earthman, Aragona Family Foundation

-

An Opportunity for Reinvention

Kristin Hull

When Kristin Hull’s family sold their business, she found herself in an unfamiliar situation: she was tapped to manage the family’s foundation—both investments and grantmaking. Kristin had built a career as a public school teacher and trader, both quite relevant to the challenge before her: how could she leverage the foundation’s resources most effectively to improve the world around her?

In 2007, Kristin attended the Global Philanthropy Forum, which held a session that encouraged foundations to pledge 2% of their endowment toward their mission. That intrigued her. “But why stop at 2%?” she wondered to herself. “Why not 100%?” This seeded her interest in impact investing.

With the foundation’s assets all in stock of one corporation, her first move was to sell the stock and begin investing the resulting cash for good. She researched community banks, eventually choosing seven that could provide a modest return while benefiting communities in need. Happy with the direct impact of helping these institutions improve financial literacy and serve entrepreneurs of color, Kristin set her sights on other ways to invest in line with the family’s values.

Kristin began working with Imprint Capital Impact Advisors, which helped expand her toolkit and learn from impact investing experts. Building from their help and gaining experience, she started doing her own due diligence and investing in deals without any help—even when more conservative investors might have paused. She explored options for fixed-income assets, then moved onto private equity. With each step, she strengthened her expertise.

Of course, not everything went just as she’d planned. Like most philanthropists working within a family or group of interested parties, Kristin sometimes faced challenges getting buy-in from other family members. During this time, she learned the most effective approach to building consensus was to identify the “lowest common denominator”—in other words, the criterion upon which everyone can agree—and begin with opportunities that fit squarely within it.

Eventually, Kristin decided to strike out on her own and continued to evolve as an investor. More recently, she started experimenting with PRIs, noting that their financial risk is inherently lower than the 100% financial loss represented by a grant. She also considers the power of early timing in funding a promising new business, which might not otherwise get off the ground. She has expanded her investor mindset to inform resources she can provide beyond money, including legal support to help with complicated documents, board member invitations, and introductions to relevant experts or partners.

These endeavors are driven by some shocking statistics: women-led companies received only 2.19% of venture capital (VC) funding in 2016, and female African-American entrepreneurs received only 0.2% of VC funding from 2012-2014. All of Kristin’s actions are part of an overall effort to support inclusion and diversity. Today, Kristin invests in women and diverse entrepreneurs through multiple organizations and approaches while building the field and educating investors.

Kristin’s story is one of her own reinvention: a family financial opportunity catalyzing her career as a pioneering impact investor. As she began, she made some smart moves.

- She started with one asset class, making investments that were straightforward and familiar.

- She sought the help of seasoned advisors early on.

- As she learned, she took ownership of her own due diligence process leading to more control and sophistication.

- And she leaned on her expertise in both social impact and financial services to inform her decisions.

Fittingly, Kristin’s entities are largely named “Nia,” after the Swahili word for intention and purpose; all of her activities are founded on the same intention: making business—and society—more inclusive, in service of helping both reach their fullest potential.

“With Nia, I am on a mission to encourage all foundations to invest their endowments in alignment with their values and their foundation goals. If I can be a part of this shift, I will feel elated.”

-Kristin Hull