Introduction

As philanthropists’ values and visions evolve, so do their preferences around how they give. Some want to leave a family legacy; some wish for anonymity; some want to involve private-sector practices in their approach. These shifts prompt their own evolution in the sector itself, which means that donors today have a wide range of options for creating the impact they envision.

The recent uptick in the number of types of charitable vehicles, though exciting, can also be perplexing, especially for newer funders. In this guide, we will help untangle different approaches for giving, how they work, and how they can function together.

As you learn about different vehicles for philanthropy, remember that none is an end in itself. The goal is to operate for impact, choosing the best way to achieve your vision. The impact you seek will determine the style of your giving.

Opening Questions

Getting Started

When considering how to give, it’s important to also think through key questions that will help define why you’re giving, alongside other considerations that can guide you to the best approach for your specific desires and circumstances. As you consider the implications of different charitable vehicles for giving, we recommend spending some time working through a series of related questions about your motivations and expectations for your personal philanthropic vision. These questions are contained in our guide “Your Philanthropy Roadmap.”

Consider how each of the following questions will affect your choice of giving vehicles:

- What impact do you want to have, and how?

- Will you be working solo, or with family members or other philanthropic partners?

- How public do you want your giving to be?

- What time horizon do you have in mind for your giving?

Ways to Give

Overview of U.S. ways to give

It can be incredibly fulfilling to personally hand a check to your favorite charity. Feeling closely connected to the mission and the people working to make it happen is very important to some donors. Indeed, until the early 20th century, this was also the only way to give. Today, many donors find that they wish to engage with the causes that they’re passionate about in a more formal way. If that’s true for you, it’s worth investigating whether a more established philanthropic vehicle—or combination of them—might provide the flexibility you need in order to achieve your charitable goals. Formal vehicles can create family legacies, or encourage new generations to give in their own way. They can provide avenues for anonymity and support for a multi-pronged approach to impact. They can also offer tax advantages, particularly in terms of donating appreciated securities to charity. Of course, you’ll need to speak with a tax professional about your personal circumstances.

Below are explanations of some of the structure your giving according to your impact goals.

Direct Giving

Some donors prefer simplicity. The simplest and most direct way of giving to a nonprofit is by cash, check or credit card. This enables the donor to have a very direct relationship with a nonprofit, and allows a high level of flexibility in responding to immediate needs. Even experienced donors giving away large sums of money sometimes prefer direct giving, and many donors who use formal giving vehicles still find themselves giving directly from time to time when the gift is outside of the foundation or fund’s defined areas.

Donor-advised Fund

Donor-advised funds, or DAFs, came to prominence in the 1990s and are now the fastest-growing charitable vehicle. DAFs are set up by public charities that act as the fund’s sponsoring organization; they allow donors to make anonymous contributions, receive an immediate tax benefit for their charitable giving, and recommend grants for the fund over time. They’re good for givers who aren’t concerned with the benefits of private foundations such as name recognition and exclusive control. Donor-advised funds offer an avenue for giving with lower costs, less oversight and effort for the donor, and more efficiency overall. You may also find value in supporting the organization that sponsors the fund (which could be, for example, a community foundation that you care about).

DAFs are particularly well-suited for those who are sensitive about privacy related to their giving. In the U.S., tax returns are not part of the public record; however, private foundations’ Form 990 tax returns are available to anyone via free services like GuideStar. If you wish to keep your giving anonymous, a DAF can offer an ideal solution: while the fund’s sponsoring organization must file a 990, all activity of the fund is aggregated, and individual donors to the fund aren’t identified. Therefore, your identity isn’t necessarily available to the DAF’s grantees, or to the public at large.

Private Grantmaking Foundation

A private foundation is the philanthropic vehicle that offers the most control, providing a framework and public face for an individual or family as they give under a personal brand. The Carnegie Corporation was the first foundation, even before the term was widely used. Its founding in 1911 is considered by some to be the dawn of intentional giving. Founder Andrew Carnegie shaped his giving around ideas that still shape foundation practices today: to do “real and permanent good in the world,” to practice philanthropy in perpetuity, and to respond to the changing needs of the world he wanted to improve. Today private grantmaking foundations are one of the most common vehicles for major donors.

If you want to work closely with other family members, build a legacy for yourself or your family, and retain complete control over how and when you give, a private foundation may be your best choice. A private foundation requires significant oversight to comply with federal and state reporting requirements; if you’re looking for a more technically hands-off approach, you might consider a donor-advised fund. Both options offer different avenues for effective and involved grantmaking. It is worth noting that a private foundation must pay out an average of 5% of its market value annually, though some limited foundation costs can be applied to this percent. Foundations must also pay 2% excise tax on investment income.

Foundations can be chartered via trust agreement or through incorporation. A foundation created under a trust agreement allows the donors to maintain tight guidelines around program priorities and governance after their lifetimes. A foundation established via incorporation provides flexibility for the foundation to change with the times and gives future generations of decision-makers more autonomy.

Private Operating Foundation

A private operating foundation can be thought of as a hybrid of a private foundation and a public charity in that it often functions as a private foundation with specific programmatic activities, devoting most of its resources to them. This kind of foundation gives a donor or group of donors significant control over program activities, as long as distribution requirements are met. (Technically, it must spend 85% of its adjusted net income, or its minimum investment return—whichever is less—on its tax-exempt activities). This vehicle is not common, but it is an excellent tool for donors that want to be very hands-on in operating a program.

Fiscal Sponsorship

If your philanthropic goals require a neutral and professionally managed entity, fiscal sponsorship can help you make an impact quickly and efficiently. With fiscal sponsorship, you can work with an existing 501(c)(3) to establish a project as a public charity, funded by you and potentially other donors. Your sponsor charity is required to restrict these donations to the established project. Fiscal sponsorship is a particularly popular vehicle for funder collaboratives, where several funders with aligned programs and/or geographies partner to make grants over a period of time with the goal of deepening their impact.

For donors, the greatest benefit of fiscal sponsorship is that the sponsor charity provides legal oversight and administrative support, leaving you to focus on programmatic activities and fundraising. The sponsor organization can also handle things like hiring staff and consultants to help carry out your mission. Using a fiscal sponsor is often much simpler than creating a new public charity, and can be used to test out a new idea and create proof of concept before doing so. Many sponsored projects that are not time-bound go on to become independent 501(c)(3) organizations after they have a proven track record.

Single-member Not for Profit LLC

Under the umbrella of fiscal sponsorship, a single-member LLC is helpful when a project needs a strong brand of its own and more independence than a typical sponsored project can provide. With this approach, a single-member LLC is established between the project and the fiscal sponsor. The project lead becomes an officer of the LLC itself and is empowered to act on its behalf. The sponsor charity still has legal oversight of the project’s activities.

The single-member LLC is a particularly good structure for artists that want to produce art for the public good. For example, Fractured Atlas, a nonprofit that provides fiscal sponsorship services, offers single-member LLCs to help fund art for public consumption. This provides individual artists with the freedom to promote their own brand, while still having the legal and financial support provided by a fiscal sponsor.

Another example of this model is ArtPlace America. Established as a 10-year initiative, ArtPlace America is a collaboration of foundations, federal agencies, and financial institutions that works to strengthen communities through arts-based community planning—an approach they refer to as “creative placemaking.” To that end, ArtPlace manages grants programs that support creative placemaking projects across the U.S. Beyond that, its practices help build the field and disseminate strategies for success.

ArtPlace America has a strong brand, an active funder’s board and a national grantmaking footprint. For them, the LLC structure provides a level of independence not available in more traditional forms of fiscal sponsorship, while still providing the benefits of legal and financial oversight from another 501(c)(3).

For-profit LLC

Operating as a for-profit LLC can give you the flexibility to make grants or investments in organizations and companies whose work supports your chosen causes, regardless of the charitable status of the grantee. Unlike foundations, LLCs can also make political donations and engage in lobbying. This control over your philanthropic activity comes at a price – the loss of a foundation’s tax deductibility, among other downsides – but can offer some funders the creativity and array of financial options that they desire. As the nonprofit sector evolves, for-profit structures are becoming more and more common, which means that the leaders in a particular field of social change may be nonprofit, for-profit, or have dual entities that work together. Likewise, for-profit LLCs, operating alone or in concert with traditional nonprofits, are changing the way that funders think about pathways to impact.

Impact Investing

Impact investments are investments made in companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Impact investments can range from pooled investments with a social screen to direct loans or investments in nonprofits or social enterprises. The choice of vehicle will influence the types of impact investing you can do.

There are numerous practical and legal restrictions that affect the interplay of impact investing and traditional philanthropy. For example, most donor-advised funds do not permit loans or direct investment in social enterprises, but many offer a socially-responsible investment choice. Recent legislative changes permit private foundations to invest in both Program-Related Investments (PRI’s) and Mission-Related Investments (MRI’s). The for-profit LLC has no restriction on the types of investments employed. Working with legal and investment professionals is recommended when incorporating impact investing into your giving strategy.

For more on impact investing, please review our guide, “Impact Investing: An Introduction.”

A note on international giving:

If you’re an American donor interested in creating a charitable entity outside of the United States, bear in mind that you may be operating not only within an unfamiliar system in terms of taxation and fiscal requirements, but also within a new set of beliefs about how philanthropy should function within society. As an example, within the European continent, several social models exist; some countries view philanthropy as a counterweight to government, some see charity as the domain of the church, and still others assume a strong welfare state. Sometimes, new agreements may make “cross-border giving” easier—such as the initiatives in Europe that allow public benefit organizations to benefit from tax relief in selected other European countries. But, as in the U.S., the one assumption we can make is that the philanthropic sector will continue to evolve; thus, it’s important to perform careful due diligence in order to understand the global implications of your charitable goals.

Vehicle Considerations

Vehicle Considerations

As you look at potential options for your giving, there are practical considerations beyond the impact you seek and the level of involvement you want. Most important among these considerations are complexity, flexibility, cost, and transparency.

Complexity

How much time and effort do you want to put into reporting and tax compliance? DAFs don’t require annual audits, as they only fund public charities; however, private foundations demand a lot more paperwork.

Flexibility

How much control do you want over your giving? With a DAF, you’ll lose control and flexibility because you won’t manage the fund’s grants directly, hire staff, or make final grantmaking decisions as you would in a private foundation.

Cost

What’s your budget for supporting your giving? It’s important to keep in mind that though private foundations provide significant benefits to donors with certain goals, their setup and operating expenses can be very expensive.

Transparency

Is it important to you that your giving is transparent? With a private foundation, you’ll file public documents that record your charitable activities. This can be a positive thing for some funders. On the other hand, those who might value personal privacy for various reasons might opt for a DAF, which can preserve the anonymity of its donors.

Comparison of Vehicles

Donor-advised Funds vs. Private Foundations

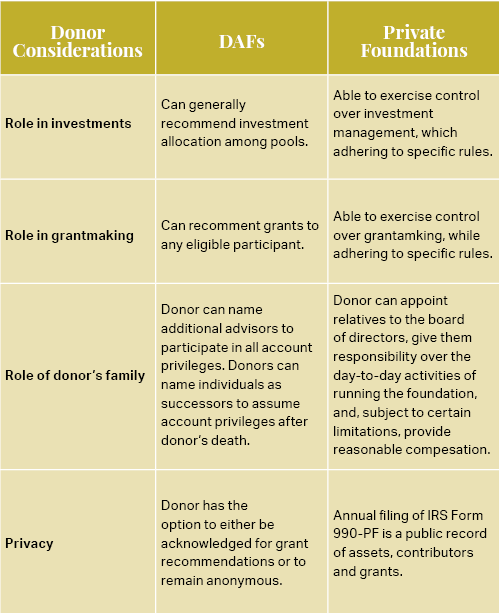

In order to highlight some of the differences between the two primary charitable vehicles (DAFs and private grantmaking foundations), we have included a quick comparison chart below.

Complementary Vehicles

Complementary Vehicles

Sometimes, as your preferences change or your family’s giving goals shift with time, the best way forward can entail multiple charitable vehicles working together—or the transformation of one into another.

You can think of it as a “portfolio approach”: as in traditional financial investing, different vehicles can help you achieve different goals simultaneously. Below, we’ll work through some examples of how this might take place.

Working together: DAFs and private foundations

If the impact areas of your giving are a bit disparate, it’s worth thinking through whether complementary vehicles can help define your giving. One philanthropic family, for example, has an established private foundation, and they don’t mind the public disclosure of their funding decisions through it. The family feels strongly about building trust and transparency in their community, and their guidelines and application process are available publicly via their website. The foundation is focused on early childhood development. Family members also care about issues outside of the foundation’s stated mandate – such as poverty alleviation and local nonprofit work – but don’t feel right about channeling non-mission related grants through the foundation. To address this challenge, the family established a donor-advised fund that doesn’t carry their name. With this combination of entities, the family finds their desired flexibility in carrying out their charitable vision.

Generational change: private foundation conversion

Sometimes, a family with a private foundation might find that they need to reimagine their giving when their children come into their own as philanthropists. One family RPA worked with had established a very active private foundation; the older generation was deeply involved in its grantmaking and processes. As these leaders retired, they became more engaged with the foundation’s grantees, taking board seats and volunteering. Once their adult children entered the picture, they wanted to make sure that the next generation felt connected to and inspired by the foundation’s mission.

After several family meetings with a philanthropic advisor, it became clear that the siblings weren’t interested in collaborative giving. The family decided to dissolve the foundation; though the older generation was a bit sentimental about its legacy, they knew that their top priority was to pass on their values of generosity and community involvement, regardless of the philanthropic vehicle. The foundation’s assets were transferred to three separate donor-advised funds, each of which would be advised by one of the children according to their individual interests. All three members of the new generation proved to be as dedicated to their giving as their parents had been, actively contributing their own money to the funds. Each DAF also made grants in honor of the foundation to past grantees in addition to newer, more aligned beneficiaries.

Case Studies

-

Two Vehicles, One Vision

Tippet Rise

The trustees of Sidney E. Frank Foundation, a private grantmaking foundation, had a vision. They saw an art center ensconced in nature, pairing the best of human creativity with the wildness of the American West. Their idea paved the way for the creation of Tippet Rise Art Center, now the world’s largest sculpture park and art center. Against the stunning backdrop of Big Sky country in Montana, Tippet Rise offers a one-of-a-kind array of outdoor sculpture and world-class musical performances.

To create this groundbreaking venue, the Frank Foundation’s leadership brilliantly employed two complementary vehicles in order to lay the groundwork for their art center. Tippet Rise Foundation is a private operating foundation, funded through grants made by the Frank Foundation. With those grants, TRF purchased the wide tracts of land required for the vast vision, bought and commissioned works of art, and built infrastructure where there had previously been none. Today, TRF continues to fund the Tippet Rise Art Center.

During the planning stage of Tippet Rise, the Frank Foundation used its resources to get to know local institutions in the area and fund them. Recognizing their outsider status, the trustees wanted to avoid launching their art center without community buy-in; they deliberately built relationships with local art and education organizations, participating in gatherings and producing concerts for friends and neighbors. They also got involved in issues that were important for their own land and that of local ranchers, such as sustainable water use and weed eradication. Instead of being seen as competitors, they became supporters of the efforts already happening on the ground.

Today, Tippet Rise’s concerts routinely sell out, and it is a destination for a wide array of cultural adventurers – as well as a favorite of the local community. By thinking critically about the structure of their giving, the visionaries behind the art center were able to create a truly unique sanctuary for the things they loved the most.

This land for us has become a metaphor, a sourcebook. We wanted to build a space where a person could have an overwhelming experience with art, if they chose to make the journey.

– Peter Halstead

-

A Multifaceted Approach to Giving

Laurie Tisch

New York philanthropist Laurie Tisch is an intriguing example of a leading giver who funds her chosen impact areas through a variety of vehicles. As a multifaceted leader and donor, Laurie’s approach lets her represent the different faces of her philanthropic identity.

Tisch grew up in what she calls a “family of generosity,” known in New York City for a wide array of giving. But she didn’t discover strategic philanthropy – that is, giving based on research and analysis, focused on strategy and goals, and committed to learning and adjusting based on assessment – until later in her life. Since then, she’s established herself as an innovative funder for social change.

The Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, Tisch’s private foundation, provides a way for her to set out and achieve her strategic giving goals, separate from the philanthropy of her family and differentiated from her personal giving. Tisch is the only board member, but the Fund has a distinct personality and a professional staff; it also funds projects in focused program areas (the arts, health, and public service). Laurie participates in several high-profile boards – she serves as Co-chair of the Whitney Museum of American Art and Vice Chair of Lincoln Center, and was the founding board chair of the Children’s Museum of Manhattan and the Center for Arts Education – and gives through her foundation to those entities.

The Illumination Fund is probably best known for its NYC Green Carts initiative, which was crafted as a response to New York City’s food deserts (areas where fresh produce is hard to find, and where obesity and diabetes are prevalent). NYC Green Carts was a partnership with the NYC Department of Health. Such public-private partnerships have been a significant component of Tisch’s work; several projects in the Illumination Fund’s portfolio have been collaborations with City entities such as the NYC Housing Authority, the NYC Department of Education, the public hospital system, and the Mayor’s Office of Strategic Partnerships. She has noted that such partnerships are not easy, and require a lot of give and take; she recognizes that she doesn’t have the on-the-ground expertise or policy experience that the partners do, but that she brings an important outside perspective that can add value.

Tisch also gives through a DAF at the Jewish Communal Fund, as do other members of her family. This gives each of them a consistent, connected way to fund Jewish causes, and separates more family-oriented giving from Tisch’s individually chosen focus areas.

There are so many great opportunities to have an impact through philanthropy, especially when you can invest your own time, foster substantive partnerships, leverage relationships, and bring your own experience to bear.

– Laurie Tisch

-

Flexibility Over Deductions

Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

After the birth of their daughter, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, announced the creation of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, dedicated to “advancing human potential and promoting equal opportunity.” (5) Chan and Zuckerberg reported their intent to donate 99% of their Facebook shares, valued at approximately $45 billion, to the Initiative, which was formed as an LLC instead of a charitable vehicle. The couple chose this model in order to retain the ability to make investments in worthy companies that advance science and education, as well as participate in related policy debates. Chan and Zuckerberg aren’t alone in looking to this model—Omidyar Network, for example, champions a hybrid approach of charitable and non-deductible investment vehicles, and Google.org operates similarly—but the prominent couple’s choice has sparked a lot of questions in the philanthropic field.

Some of those questions are: what is CZI’s exposure to legislative change? What impact will it have on the charitable world? Will it make good on its long-term promise to work on social change-related causes? As Gene Takagi of NEO Law Group points out, “Ultimately, they can turn it into a pure investment vehicle…it’s certainly within their power and control to do so.” Takagi also wonders if this development will spark more competition for talent between future philanthropic LLCs and traditional foundations. At this point, the results remain to be seen, but CZI definitely represents an ongoing integration of public and private approaches to funding the brightest ideas for improving the world.

What’s most important to us is the flexibility to give to the organizations that will do the best work—regardless of how they’re structured.

– Priscilla Chan & Mark Zuckerberg -

Balancing Personal and Collaborative Giving

Denise Sobel

New York philanthropist Denise Sobel’s chosen impact areas are women’s health and the arts, focused on New York City. She specifically looks for ways to support the practical needs of the organizations she cares about, valuing a “behind-the-scenes” approach that might not appeal to donors who wish to be more visible. In addition, she often approaches a potential grantee with openness, asking what its most pressing issues are, so that she can provide crucial funding that might not be obvious from the outside. In this way, her personal giving can be intuitive and flexible.

To complement these efforts, Sobel founded the Tikkun Olam Foundation to practice philanthropy collaboratively with her daughter and another family friend, seeking to create strategic and focused program areas. TOF’s first pool of funding came from the assets transferred after Sobel’s family foundation closed. With this dual approach, she can make decisions both individually and collaboratively.

Moving Forward

Moving Forward

As a philanthropist in a rapidly changing charitable landscape, you can consider a wide range of operating models in your giving portfolio. This overview of the main charitable vehicles is meant to pique your curiosity, provide some questions to help guide you, and inspire you to think flexibly and creatively about your giving. Once you feel comfortable with the basics, it’s always wise to discuss your options with an attorney or trusted advisor. Making these decisions with care will help you operate for impact, efficiently and effectively creating the change you envision.